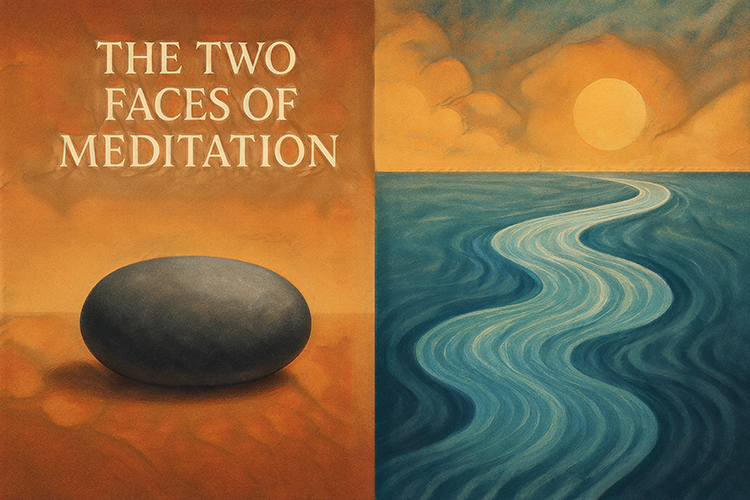

From the polished calm of modern practice to the boundless depths of the ancient path, a journey through meditation’s two faces — and the ocean where they meet.

Modern meditation often polishes the mind into stillness; ancient meditation seeks to dissolve the mind entirely. One trains awareness to rest in the moment, the other carries it beyond all moments, into the formless union the sages called Samadhi. This is the meeting place — where technique falls away and only truth remains.

Q: What is true meditation, beyond the contrived techniques we’re taught in yoga classes and seminars?

A:

True meditation begins when the doing stops.

It isn’t posture, breath control, or the recitation of syllables for their own sake — though these may serve as doorways. It is awareness resting in itself, not chasing, not resisting, not trying to become.

Thoughts drift in and out like birds across an endless sky. Sensations ripple and dissolve. Even the subtle thought “I am meditating” fades until there is no meditator, only being.

Here, meditation is not an escape from the world but an unfiltered intimacy with it — no preference for silence over sound, no clinging to the soft over the sharp. You are not “arriving” because you never left.

Q: But isn’t this what we’re doing in yoga and mindfulness classes in the West?

A:

Not quite.

What you’ll often find in the West — whether in a yoga studio or a corporate mindfulness seminar — is meditation as technique:

- Breath counting for relaxation.

- Visualization for focus.

- Mantra for calming stress.

These are useful tools for health, emotional balance, and clarity. But they are, in the ancient sense, preparatory.

In the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, for example, meditation (dhyana) is the seventh limb in an eight-limbed path. It is not a stress-management strategy — it is the deep absorption that arises once the mind has been stilled through ethical living, disciplined practice, and concentration (dharana). And beyond even dhyana lies samadhi: the dissolving of the self into pure awareness.

Western adaptations tend to focus on the outer rungs — because they’re accessible, measurable, and beneficial in daily life. Ancient meditation aims for the summit — the total transcendence of personal identity.

Q: Then what was Ramakrishna doing when he slipped into bliss during meditation?

A:

Ramakrishna’s “meditation” was already in the territory of samadhi. He wasn’t climbing the rungs — he was already living at the top of the ladder. For him, meditation was simply the gentle closing of the eyes before the self dissolved into the ocean.

In these states:

- There is no “Ramakrishna meditating.”

- Bliss is not felt about something — bliss is the nature of reality itself.

- Time and body-awareness fall away, sometimes for hours.

The ancient traditions hold this as the highest fruit of meditation — but also caution that it comes not from perfecting a method, but from the ripeness of the soul and the surrender of the “doer.”

Q: So does meditation always lead to Samadhi?

A:

It can — but it’s not automatic. In the ancient vision, the techniques (whether concentration, breath, mantra, or mindfulness) are the boat. Samadhi is the shoreless ocean.

Western meditation often keeps the boat tied to the dock — you row in circles, learning calm, focus, and presence. Ancient meditation sets the boat loose, and sometimes the ocean’s current takes you all the way.

For most, meditation is the clearing of the mind’s waters until they reflect the Infinite. For the ripe soul, that reflection gives way to immersion — the drop awakening as the ocean.

When the doing ceases and the doer dissolves, meditation is no longer something practiced; it is reality recognizing itself. This is the meditation the sages meant — and it is of a different order than the guided relaxations we usually call by that name today.

Addendum: Where the River Forgets Itself

The West has made meditation a kind of polished stone — smooth, practical, easy to hold. It rests well in the hand, and it can soothe the restless mind. But in the ancient way, meditation was not something you held. It was the river that swept you away.

There is a threshold beyond the breath, beyond the mantra, beyond the cultivated calm. Step over it, and meditation is no longer a practice — it is the undoing of the practitioner. Here, you do not “watch the thoughts” because the one who watches is gone. Here, there is no “state” because all states have dissolved into the stateless.

The sages say this is samadhi. But names matter little when the river has already carried you into the ocean. And once you have tasted that ocean — as Ramakrishna tasted it again and again — even the busiest marketplace hums with the same eternal stillness.

Western meditation often teaches us to polish the stone. Ancient meditation teaches us to throw it into the river, and follow the ripples until there is no more “you” to arrive.